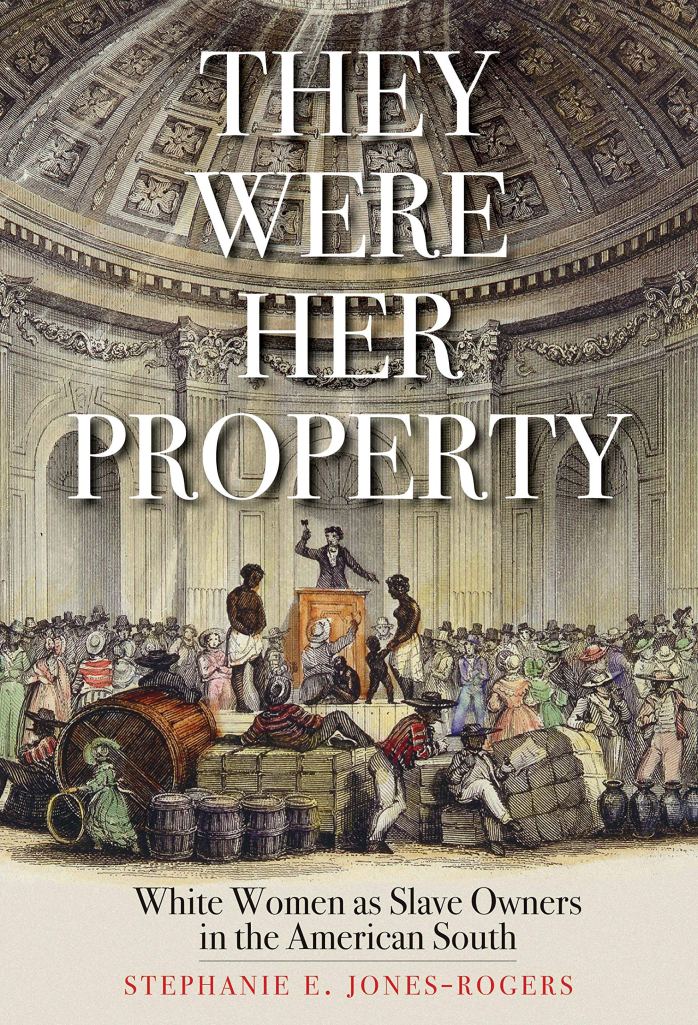

Book Review: They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South by Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers

I wasn’t surprised by how thought-provoking I found They Were Her Property: White Women as Slave Owners in the American South by Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, Associate Professor of History at the University of California, Berkeley. I bought this book in early 2019, but only started to read it in earnest this past January 2020, and I deeply regret letting such an important text stay on my shelf unread for so long. Part of the issue was that my life has been particularly busy in the past year, but another reason is that the subject matter of this book is traumatic, and I needed to be in a headspace where I was capable of taking in that trauma without letting it adversely affect other areas of my life.

Many of the traumatic elements of the book will be familiar to anyone who has studied the history of slavery in the United States: the cruel ways in which slaves were mistreated via brutal physical and psychological punishments, rape and torture, the way that they were bought and sold as property rather than autonomous beings, and the way that those transactions destroyed families and communities, tearing apart bonds between parents, children, lovers, and other essential human connections. What is distinct about the lens that They Were Her Property takes on is that the book directly grapples with the way that white women participated in the slave trade and the rights, responsibilities, autonomy, and distinct power that they had over their slaves — their property — and how owning people gave them an advantage in the world that has been historically ignored, glossed over, or simply denied despite evidence to the contrary.

One of the topics that They Were Her Property investigates is the ways in which white women owned slaves as distinct property from that of their husbands, and were allowed the power to control the slaves how they saw fit both in their treatment and in negotiation regarding their purchase and sale — contrary to the popular belief in the formal law that all women’s property was dissolved into the estate of her husband upon marriage. The book also discusses how, far from being ignorant to the details of the slave trade, many women had front row seats at auctions, and readily participated. Another point that Jones-Rogers brings up is that mistresses are on record as at times having been even more brutal and shrewd than their husbands when it came to their slaves, while others made sure that the slaves that belonged to them were kept to a certain standard, while slaves belonging to their husbands were his responsibility. And in her discussion of the Civil War, Jones-Rogers discusses how women slaves owners who supported the Union and who supported the Confederacy alike fought to keep their slaves, fighting the war in a different dimension, but fighting all the same, and how some of them cut their losses by selling their slaves or getting compensation from the government, while others later lamented the loss of their slaves leaving them destitute.

The above barely constitutes highlights as there truly is a wealth of knowledge in They Were Her Property — a depth and breadth of research for which I absolutely commend Jones-Rogers. Upon finishing this book I felt very much enlightened about this side of slavery about which I had previously been woefully uninformed, as the traditional narrative I had learned in my AP US History class, or any of my primary and secondary school education, never touched on this subject with any kind of depth. A highly recommended read.

Cheers,

Talia