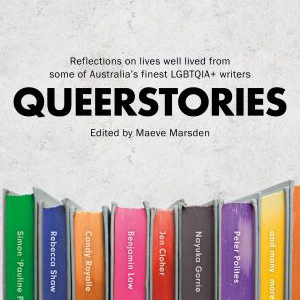

Book Review: Queerstories, edited by Maeve Marsden

Living in the United States, it can sometimes feel as though there is a drought of information about people within other countries, particularly those who come from marginalized backgrounds. In light of this, one book that has provided me with a kind of water is Queerstories: Reflections on lives well lived from some of Australia’s finest LGBTQIA+ writers, edited by Maeve Marsden. The book is a collection of short stories in the form of narrative nonfiction, each of them as unique as they are wonderful, giving windows into many — but by no means all — ways of being queer.

Queerstories as a book grew out of the Queerstories storytelling event hosted by Marsden, which began in Sydney and has now spread to other areas of Australia including Melbourne and Brisbane. I first encountered Queerstories via the popular podcast of the same name, episodes of which feature recordings from the live events. The podcast was recommended to me by one of my good friends, and I was instantly hooked, listening to dozens of episodes in a matter of days.

The personal essays within Queerstories are full of humor, emotion, and devotion to human connection. No two stories were exactly alike, and cannot be characterized in exactly the same way, because they each made their mark in ways big and small. I mentioned before that these stories showed different ways of being queer, but they also showed different ways of being human. In addition to the diversity regarding gender and sexual orientation — two terms that in their own way form a kind of restriction — the contributors to this anthology were also from a variety of racial and ethnic backgrounds, telling their stories as queer Australians, yes, but with many also having roots in other countries and other communities.

Furthermore, these stories reject some of the narratives that we are so often told regarding the way that queer folk and those with marginalized identities exist and live in the world. In her essay “A shit queer” Kelly Azizi rejects the idea of fully immersing oneself in a community, determining her own way of seeing the world. Jax Jacki Brown spends her essay, “Bodily interventions” discussing the real problem of accessibility and discrimination, and articulates the truth that “Queerness and queer family-making is about more than love and sexuality; it’s about access, inclusion and equality” (151). Another contributor, Vicki Melson, asserts the truth of how no one has the right to put parameters on queerness and I love her for it. These are but a few examples of some of the powerful lessons taught in the book.

And yet this book is more than just an educational experience about the inner lives of queer folk; it’s a celebration of those lives. While it is true that there are some stories that are on the sad side, some stories that talk of the pain of separation or disownment, there are also stories of happiness. There are stories of how life goes on, how family finds a way to work itself into a happy equilibrium. Marsden writes in her own contribution, which comes at the end of the book, that the stories of when families fall apart are not the ones that queer communities want to hear because the blame would fall upon queerness, rather than on a failure of human connection that in reality occurs just as often in heterosexual relationships. But not including the bad times would not be true to the way that queers live our lives, just like any other grade of human. And while not always, sometimes the bad times do lead to a happier resolution.

The overall message of this text is one of uplift. No two stories tell it the same way, but the feeling achieved at the end of reading this anthology was one of peace and contentment. At the same time, this text dives into some very real issues having to do with the representation that queer folk and those with marginalized identities receive now and have received in the past. In her letters to the late Audre Lorde, Candy Bowers writes about how, as a multiracial woman, there were no roles for her as an actor, and no one was going to write a part for her, so she had to write one for herself (and she did so fabulously). Lack of representation is a theme in many of these stories, but it certainly isn’t the only one. Another is the ways in which unconventional families can in many ways be some of the most rewarding. “The everlasting open family” by Paul van Reyk is an example of how families can grow and prosper, even when they do not fit into standard social norms.

As we reflect upon the surge of queer representation in our literature and other forms of popular media, its important to keep in mind narratives such as the ones within Queerstories — that is to say that there is no one queer narrative. Every person has their own story and moves through the world in their own way. Queerstories as a literary work shines a brilliant light on twenty five of these stories, but there are many more out there, just waiting to be discovered.